Artist Statement - Marc Lancet

“By resonance I mean the power of the displayed object to reach out beyond its formal boundaries to a larger world, to evoke in the viewer the complex, dynamic cultural forces from which it has emerged and for which it may be taken by a viewer to stand. By wonder I mean the power of the displayed object to stop the viewer in his or her tracks, to convey an arresting sense of uniqueness, to evoke an exalted attention.”

The focus of my work has been increasingly centered on studio process. I can not apply wonder and mystery to a work like a coat of paint. Rather if I work with wonder and mystery in the studio - with an inspired attention - then often the works I create are imbued with these qualities. I seek paradoxically to surprise myself when I work. I avoid over planning in favor of discovery. I trust instinct, celebrate whim and discourage certainty. I bring to the studio my own fascination with the "complex, dynamic cultural forces" and a trust that these interests will emerge in the work without my forcing them. I go to the studio to discover rather than to work out some pre-ordained plan. I endeavor to create art in which conceptual integrity and visual attributes are intertwined, inseparable.

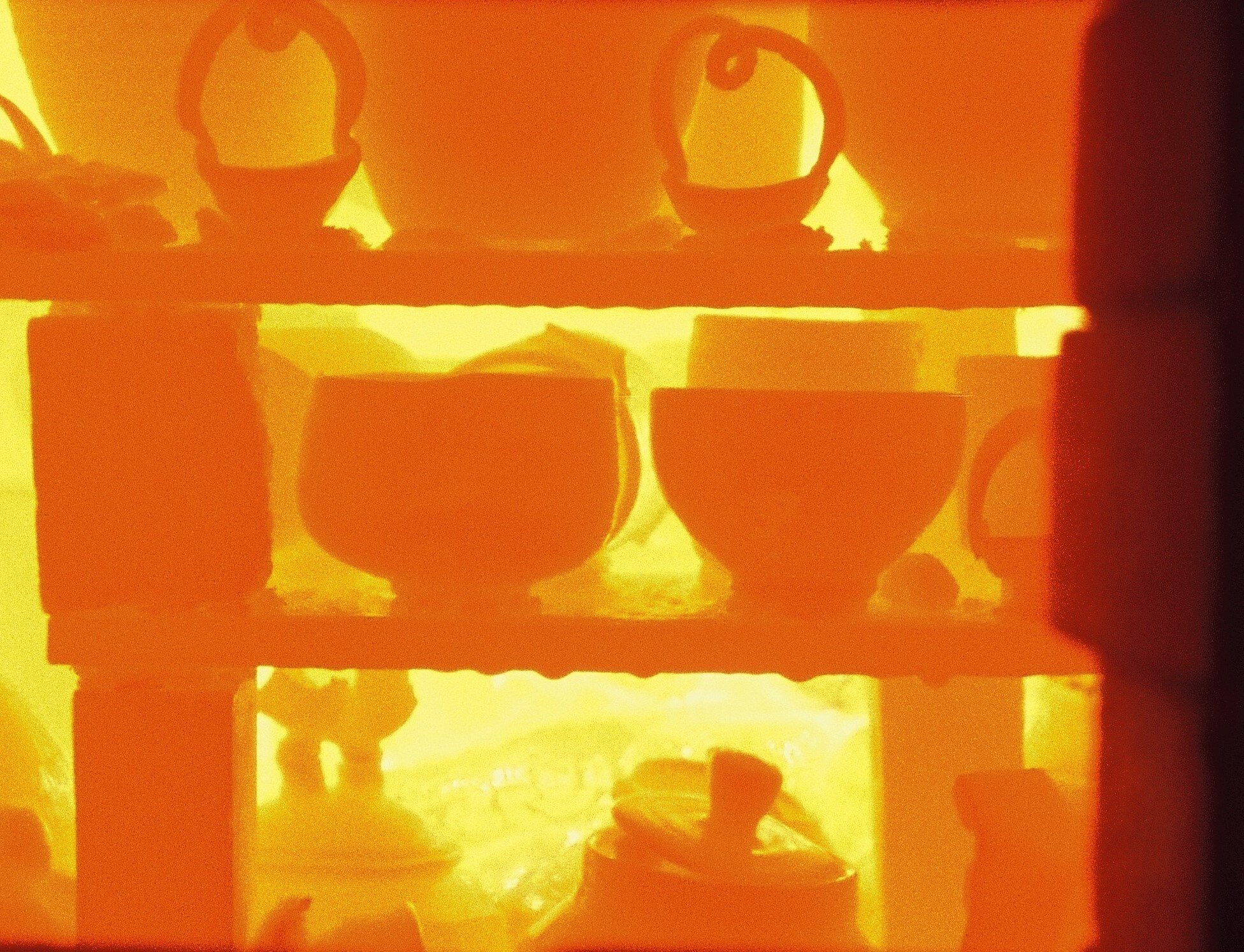

Matcha Jawan (tea bowls)

Matcha jawan (tea bowls) are very near to the heart of my work. In a conversation with my friend the painter Adam Wolpert we discussed the meaning of tea bowls as a symbol, since he has been working on a series of paintings that employ a “portrait” of one of my tea bowls as a recurring image. I managed to summarize my continuing fascination with the form in one sentence. The tea bowl is at the heart of the Tea Ceremony; the ceremony which invites us to wake to the world.

My brother Barry Lancet has written eloquently of the significance of the Tea Bowl.

“The Japanese fascination with tea bowls has always been a puzzling one to many Western ceramic enthusiasts, yet a close look at both old and new pieces reveals that there is much to be said for these deceptively simple pieces. In Japan, the tea bowl has become a sort of artistic Holy Grail. Over time, the tea bowl’s central position in the tea ceremony has made it the nexus of functional, aesthetic, and spiritual demands, prized older works are breathtaking examples of the finest that Japanese ceramic art has to offer - at once noble and serene - though it must be pointed out that many inferior bowls are treasured for their lineage (that is their ‘Tea History’), a fact which clouds the issue in Western eyes.”

“If you can make a good tea bowl, you can make anything’ is almost an adage in the Japanese ceramic world and there is more than a grain of truth in it. To bring together the lip, the inner surface, the outer profile, and the concluding foot with the right mixture of clay, glaze and fire to produce the elusive balance of utility and grace is not a feat to be taken lightly. To bring them together with a touch of spirituality is magic.”

“The successful bowl will have an inexplicable serenity to its stance as if it knows what it is about.”

- Barry Lancet, from his essay Shiro Tsujimura

Matcha chawan (tea bowls) are very near to the heart of my work. In a conversation with my friend the painter Adam Wolpert we discussed the meaning of tea bowls as a symbol, since he has been working on a series of paintings that employ a “portrait” of one of my tea bowls as a recurring image. I managed to summarize my continuing fascination with the form in one sentence. “The tea bowl is at the heart of the Tea Ceremony; the ceremony which invites us to wake to the beauty of the world.”

Mizusashi (water jars) and Hanaire (flower vases)

Mizusashi and Hanaire – the bold asymmetrical water jars and flower vases, like the tea bowl, stem from 16th century tea ceremony aesthetics. Yet, when I make them I find they share much with the best of the American action painters of the 1950’s and 1960’s. The fluid masses and gouged sweeping strokes are done in an instant. An instant when the potter, drawing on years of experience, is completely in action responding to the material as it takes shape. There is no place for hesitation, insecurity, or pre-determination. These would produce a weak, insubstantial result. So in a water jar we can find, perhaps, one of De Kooning’s women. Or in a flower vase we are taken back to the vigorous movement of Jackson Pollack over a canvas on his studio floor. These pieces register vigorous movement, informed by years of experience.

Both forms are studies in balanced asymmetry. A potter composes the spinning cylinder of clay just as a painter approaches a blank canvas; each gesture, bulge of form, compression of cylinder, or mark informs the next. Viewing a composition, what is absent (the open space between marks and gestures, the proportions) is as important as what is present.

Hanaire, are meant to perform as the beginning of a composition which is completed by the Ikebana. Ikebana is often translated as flower arranging but perhaps better thought of as sculpture employing biological materials. The whole composition is framed often by the Tokonoma (the quiet nook in a Japanese tea house or home where the arrangement is placed for meditative contemplation of it’s beauty and natural qualities).

In my studio I embrace equally, the over 400 years of Japanese tea aesthetics and contemporary art. My pottery and my sculpture are informed by both. I hold the deepest respect and appreciation for the aesthetics of the tea ceremony and I benefit from the Japanese practice of innovating from within that 400 years of tradition. I am equally engaged in the pursuit of discovery and original experience inherent in contemporary art making. These seemingly contradictory cultural forces find harmonious coexistence in the pottery forms and sculpture that I create.

The Japanese Tea Ceremony

(Chanoyo and Chado)

The human quest to transform the spirit, the yearning for transcendence, the urge toward enlightenment is at the heart of Chado or Chanoyu (the Japanese way of tea). This16th century Zen inspired tea ritual seeks the elevation of the human spirit though art.

Central to Japanese traditional arts is the concept of “Do” or way. Through practicing a specific art with integrity, the artist is transformed. As the artist’s abilities develop and their insights magnify they come to know the universe and their place within it.

Artists around the world come to know this transcendent experience inherent in a life of art. So to, those who embrace the appreciation of art, are transformed by their immersion. Chanoyu’s main vehicle for transcendence and transformation is beauty – the sublime. And each tea bowl, each flower vase, each water jar is an invitation to all to wake to the beauty in life in this present moment.

The creation of tea ware for the Chanoyu brings many benefits to the Western artist who attempts it. To make a tea bowl is to enter into an ongoing dialogue over 450 years old. Originality is expressed in the way each artist combines elements of function, tradition, spirituality, philosophy, history and of course form and surface. There is vast opportunity for individual expression residing within these ancient traditions.

Creating tea ware deepens my understanding of Western art traditions and their role in my contemporary sculpture. Striving to make a tea bowl of merit teaches me more about sculpture than almost any other aspect of my art training.

An artistic temperament seeks new understanding, unfamiliar territory; embraces the unknown. This is perhaps why so many Japanese ceramic artists I have encountered in my travels are making art responding to contemporary western art ideas and practices. This too is how I have come to work within the ancient and honorable traditions of Chanoyu.

Art is a required nutrient for human existence. Like vitamin C. Do without it and you get scurvy. Without art, the human spirit withers, becoming smaller, feeling less, seeing less, experiencing less. Without art, the human spirit fails to achieve its potential. As with many maladies stemming from nutrition deficiencies; the affects are subtle, slow, incremental, and difficult to notice as the human spirit diminishes. Fortunately art and artists abound and the cure is everywhere. Have you had your recommended daily dosage of inspiration?

-Marc Lancet